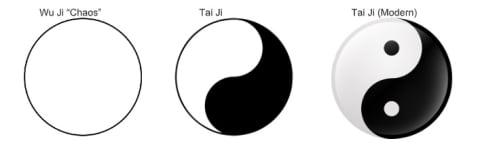

Yin-yang represents the universe creating itself from chaotic Wuji energy and transmuting it into order, or Tai Ji—the great polarity. So the yin-yang symbol represents creation theory or the “big bang.” It begins with nothing and transforms into everything. It’s impossible to know the true origin of yin-yang, though symbols representing yin-yang were present during the Neolithic period (3400 B.C.). Yin-yang is also represented in the I Ching, or The Book of Changes, a Chinese divination text that dates back to 1000–750 B.C. and is still used today. This theory appears in literature during the Yin and Zhou dynasties (1047–256 B.C.), an influential time period known as the start of Confucianism and Daoism. As such, yin and yang theory is rooted in many schools of thought, and you can find examples of it everywhere. Women are associated with yin because the menstrual cycle typically lasts 28 days, like the moon cycle. In Chinese, the “essence,” or substance, that sparks the menses is called the Tian Gui, or heavenly water, which signals the transformation from a girl to a woman with the ability to bear children. When combined with yang, it bears the potential for life. Yin is associated with the winter season, while yang is more summer. The autumn is more yin than summer, but more yang than winter. Here are a few examples of what can happen when yin and yang are out of balance: When the elements of yin and yang are in balance in your environment, there is a good flow of chi that promotes health, wellness, and longevity. When it is out of balance, your surroundings can feel stale and uninspired. By destroying nature, we are in a sense destroying ourselves. We would be better off adapting our lifestyles to be in alignment with the seasons and cycles of nature, versus resisting or fighting them. In Chinese medicine, certain illnesses are seen to be more prevalent during different seasons, corresponding with yin-yang imbalances within the body. Over time, too much yang activity interferes with the body’s biological clock, or circadian rhythm, which can make you more susceptible to illness2. Stop believing the myth that productivity means constantly expanding, increasing your output, pushing your limits, and overriding your natural needs for recovery, rest, and rejuvenation. Never underestimate how important rest is for the body and mind. These more yang approaches to exercise are counterproductive. Ultimately, they’re just recipes for injury. Instead, try to work movement into your entire day and check in with what your body needs before choosing an exercise. To find balance, block time on your schedule for activities that are more yin in nature: breaks in the day when you can eat, breathe, meditate, and re-center. Get in the habit of taking relaxing baths and thinking about three things you’re grateful for before going to bed (the earlier, the better!). Gratitude is the practice of receiving, and it is therefore very yin. Ending your day with gratitude will also help you stop your mental chatter and encourage restful sleep. She received her Masters of Oriental Medicine at Tri-State College of Acupuncture, and currently serves as a senior clinical faculty member there. Tsao is a NCCAOM (National Certification Commission for Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine) Diplomat in Acupuncture and Chinese herbal medicine. She has completed post graduate studies in classical Japanese herbal medicine known as Kampo and doctoral level training and certification in Sports Medicine Acupuncture®. An experienced and highly trained licensed acupuncturist and healer, she serves patients in the New York City area and continues to study the ancient healing arts and the art of classical Chinese medicine. Much of her work focuses on teachings of master practitioner Kiiko Matsumoto.